Since I am now posting regularly over at Murder Is Everywhere and seem to be incapable of blogging more than once a week (if that) I've decided to cross-post those pieces here, after a suitable interval...

ORIGINALLY POSTED JAN. 6 ON MURDER IS EVERYWHERE

I’ve had the honor of guest-posting here several times, but since this is my first official post, I thought maybe a little background about how and why I ended up writing books set in China was in order. So…

My first time in China was 1979. I was twenty years old. This was shortly after the Cultural Revolution, at the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s opening to the west and economic reforms, and while I was there, China and the US normalized relations—I attended a picnic at the Ming Tombs celebrating this occasion. Leonard Woodcock, the head of the United States Liaison office in Beijing (no ambassador until post-normalization) was there, and we all got little US and China flag pins as mementos. A small crowd of kids from a nearby village gathered to watch. They all wore clothing that was much patched and worn, and either too big or too small for them, and they were nearly as shy as a herd of fauns, scattering if any of us stepped in their direction.

I can’t say that I had culture shock (a term much in vogue in the 70s; does anyone ever use it these days?). Everything was so completely different that I just sort of accepted it and moved on.

(photo from

this photo essay)

That was the time when everyone wore blue and green clothing, and when you bought that clothing with coupons, because there was still rationing. A time when there weren’t many restaurants that had survived collectivization and the Cultural Revolution, or many places you could buy much of anything, period.

You accepted that as a foreigner you were going to be watched, by the authorities and by people who had just never seen anyone like you before. You learned “the 3 Ms” from other expats,

“Meiyou, Mingtian, Meiguanxi” – “Don’t have,” “Tomorrow,” and “It doesn’t matter.”

You accepted, then railed against, then surrendered to, the Great Wall of Bureaucracy and a system that seemed determined to make everything as difficult as possible. Learned that decisions were often arbitrary, and that “the situation” would change from day to day. That’s just how it was.

I stayed in China six months. I taught Conversational English for a quarter and traveled for a month, mostly during Chunjie, “Spring Festival,” aka Lunar New Year. I vowed never to do that again. In China, this is when everyone is more or less obligated to return home to celebrate with family. This year,

Xinhua estimated the number of passenger trips on trains, planes and boats to reach 3.41 billion around the holiday, and while I’m sure there was nowhere near that volume in 1980, it was still pretty hairy. I was on a boat going down the Yangtze during this time, and I watched in wonder as people boarded carrying boxed color TVs and dining room chairs on carry-poles, doors on their heads, just crazy amounts of stuff, and before long our boat looked like we were fleeing an invading army.

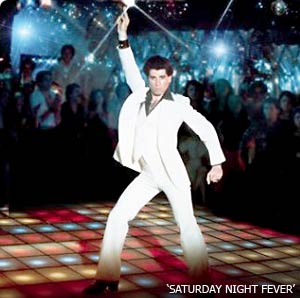

Sometimes I was pretty sure that the invader was me. There were so few foreigners in China at the time, and so few of them were Americans. American pop culture had barely begun to penetrate, and it was mostly bootlegged tapes of “Sound of Music” and a weird fondness for “Home on the Range” (a popular choice for the 6 AM morning wakeup medley on Chinese trains, right after “The East Is Red”). All of sudden, there I was, the first American most of the Chinese people I encountered had ever met. The person my students asked about the American Constitution and Bill of Rights; also, “the Disco Dance.” I worried about saying the right thing, about setting a good example.

And I wondered, was the inevitable invasion of American pop culture a good thing? It was like I’d beamed down from the Starship Enterprise (I was a huge Trekkie), and I was violating the Non-Interference Directive just by being there.

Not that I was any kind of Communist. No pictures of Chairman Mao on this kid’s dorm wall. And after spending six months in a place that had been devastated by the Cultural Revolution, I didn’t have a lot of sympathy for utopian movements, or the manipulation of such sentiments by a fratricidal leadership at war with itself.

(by photojournalist Li Zhensheng -

check out his story!)

I remember leaving China, crossing into the New Territories, on my way to Hong Kong. I remember that the officials at the border, Customs or whatever they were, demanded that we pay some additional exit fee. I can’t remember how much, but it seemed like a lot of money at the time to a student who had only been a “Junior Foreign Expert” and was paid about a third of what the real “Foreign Experts” made, who still needed to buy a plane ticket home.

I was so ticked off. One last bit of b.s. I hadn’t expected, from a system that seemed designed to screw with people, because it could. “I am so glad to be leaving this place!” I told my friend. “I can’t wait to get across that border.”

I remember, when I did, I turned around and looked back at the country I’d just left. We were surrounded by green, out in a No Man’s land of countryside between the People’s Republic and the British crown colony.

You’ll be back.

I swear it was a voice in my head, clear as anything.

No way, I thought. No way.

Score one for the voices in my head.

Lisa—Sunday